Archaeology After 1867

In 1915, George G. Heye excavated Mound No. 3 for the Museum of the American Indian. Heye recorded his findings and made various observations regarding the dates and cultural affiliations of the artifacts that he uncovered. He also noted the erosion that was occurring at the riverbank adjacent to the site.

The Cherokee Project: 1965-1966

"To define Cherokee culture at the contact period and see whence it came from" - Joffrey Coe, on the objective of the RLA's Cherokee Project

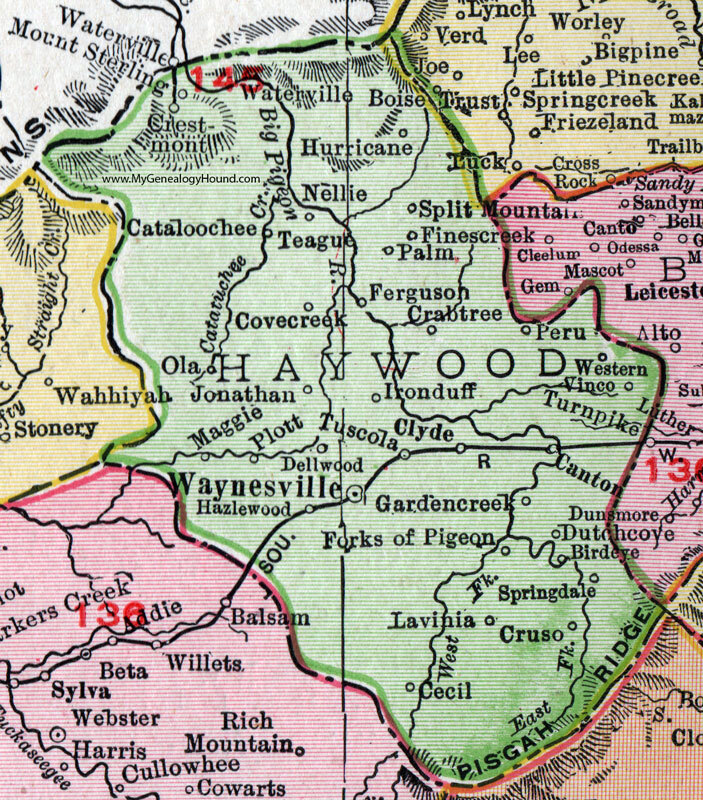

In the early 1960's, researchers from the University of North Carolina Research Laboratories of Archaeology conducted pedestrian survey sites throughout nine counties across southwestern North Carolina. In 1965, Clarence Cathey, a property owner in the neighborhood that exists on the Garden Creek site, was building his home and used dirt from Mound No. 2 as fill. The Cherokee Project field director, Bennie Keel requested to investigate the remaining sections of the mound and Cathey agreed. With Cathey's permission, Keel was able to begin the first formal research-driven archaeological excavation of the site.

Findings

The Cherokee Project at Garden Creek’s Middle Woodland component focused on excavating the remaining portion of Mound No. 2. Keel used the data collection that he obtained through excavating the mound to create a ceramic chronology for the Appalachian Middle Woodland Period. Keel created a timeline of "diagnostic" characteristics for archaeologists to use in order to date the ceramic artifacts that they excavate from across the Appalachian Through the combination of meticulous excavation, recording, and the nature of the artifacts found, Keel determined that Mound No. 2 dated to the Middle Woodland Period, not the Mississippian Period. The conclusion that the Garden Creek site had an earlier component than historians and archaeologists had initially believed was a significant realization that contributed to further research regarding lifestyles and cultures of people living in the Middle Woodland Period. Keel's findings put Garden Creek on the map of both important sites in the southeastern United States. Keel and his team of fellow archaeologists also recovered a variety of non-local artifacts, indicating that its Middle Woodland inhabitants were involve in long distance exchange and interaction. This observation ws further examined by the Garden Creek Archaeological Project in 2011-2012.

Althuogh Keel and his team primarily focused on Mound No. 2 at Garden Creek, he was also determined to understand the extent of occupation of the entire Middle Woodland component of Garden Creek. Based on the various artifacts that he excavated, their quantity, typologies, and spatial distribution, Keel made the claim that there was a larger, underlying Middle Woodland village at the site that was heavily occupied at the time of its use. Unfortunately for The Cherokee Project at Garden Creek, further residential development in the neighborhood began, and Keel determined that the underlying village was covered, or even potentially completely destroyed, by the new contemporary structures. The Cherokee Project at Garden Creek ended, but archaeologists were not completely finished with attempting to learn from the site See "2010-2012 GCAP Excavations" to learn about the reopening of an archaeological project at the site!

Although Keel and his team primarily focused on Mound No. 2 at Garden Creek, he also tried to document the extent of occupation of the entire Middle Woodland component of Garden Creek. Based on types and spatial distribution of artifacts at the site, Keel argued that there was a Middle Woodland village Garden Creek, the evidence of which had been largely destroyed destroyed by modern residential development in the neighborhood.

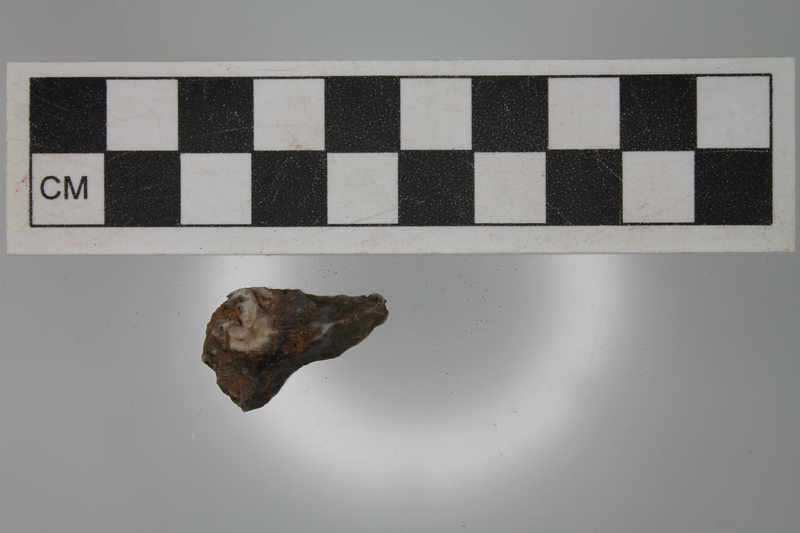

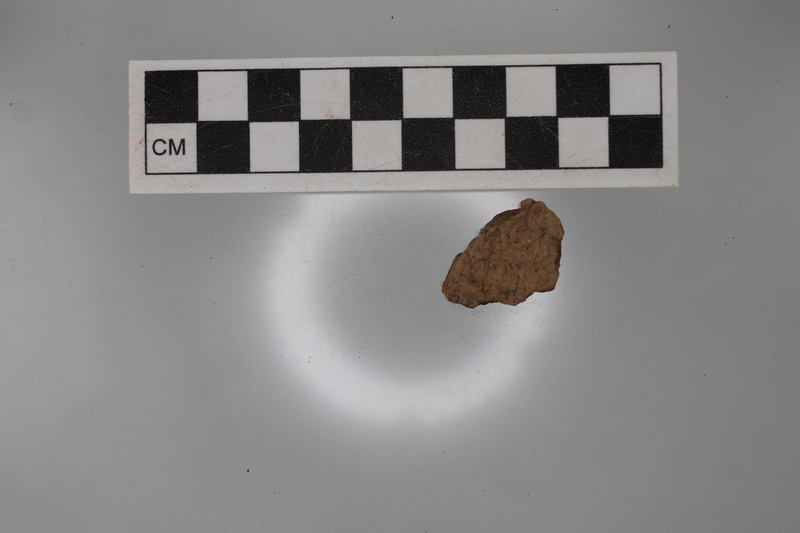

Identifying Where, When, and Who with other Components

As seen by the potsherds in the above collection, as well as the interactive sherd on the left, many artifacts have distinct designs and uses that help archaeologists indicate when and where they might have come from. Information such as the Appalachian Middle Woodland ceramic typologies, created by Keel after UNC RLA's excavation of Garden Creek, allowed the later Garden Creek Archaeological Project to make further claims regarding the likely timing of the site’s occupation and interactions among different people in the past. Although inferring time and cultural connections from potsherds is frequently practiced by archaeologists, it is important to recognize that artifacts do not equal a people. While humans certainly shape the material world, assuming that a people are straightforwardly identifiable by the goods they produce, and use assumes that cultures are static and that people participating in the same cultures always do exactly the same things. We know both of these assumptions are not true! It is critical that archaeologists adopt a nuanced approach to artifacts that acknowledges the agency, creativity, and context-dependency that creates the patterns we observe in the present.