Early Challenges and Burgeoning Social Change: 1917-1940

World War I and Spanish Influenza

Appalachian Training School faced early challenges due to people returning from World War I and spreading Spanish Influenza. The United States entered World War I in 1917. Under Herbert Hoover's presidency, the Food Administration was established to help the military by freeing up food supplies and assisting with the food scarcity in Europe. Constituents were urged to alter their food habits by buying locally, using alternative ingredients, and growing their own "Liberty Gardens."

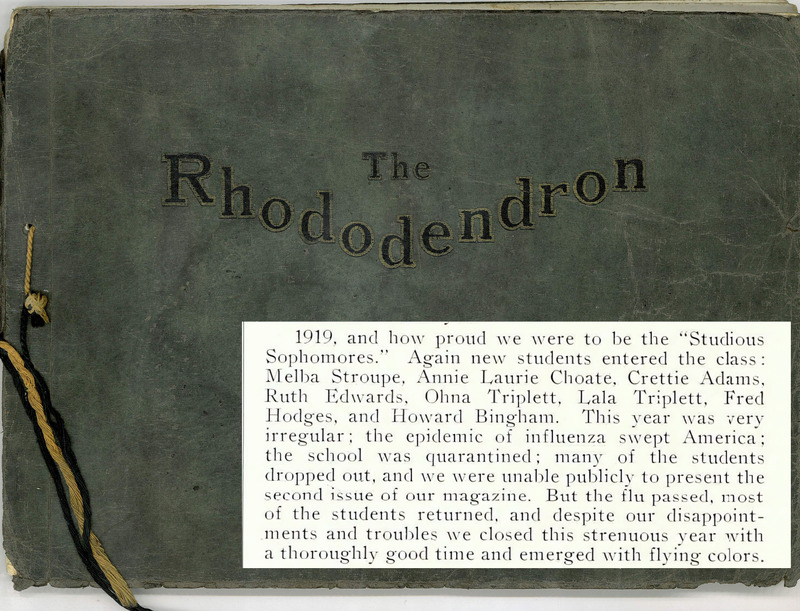

Appalachian Training School was quarantined in 1918 due to the Spanish Flu outbreak. No one was allowed to enter or leave campus. Additionally, there was a teacher shortage in North Carolina following World War I, and the North Carolina General Assembly encouraged the school to train elementary school teachers.

The school underwent two name changes during this period: Appalachian State Normal School (1925–1929) and Appalachian State Teachers College (1929–1967).

The Great Depression

When the Great Depression began, the school kept costs down by sourcing food from its farms.

Burgeoning Social Change

The college was a much more conservative place in the 1920s and 1930s. University administration practiced in loco parentis and acted in control of a student in place of a parent. Under the leadership of B. B. Dougherty, female students were required to keep strict curfews and were not allowed to socialize with male students. A creek separated men's and women's dormitories, and it was against the rules for women to cross the stream. It was rumored that Dougherty would walk along the creek looking for rulebreakers. The old administration building even had separate entrances marked "Boys" and "Girls." Students could sit in co-educational classrooms but were not allowed to mingle while entering or leaving class. In another effort to separate the sexes, administration scheduled times for each group to exit the cafeteria when prompted by a bell. A grade was assigned for human behavior.

In 1935, led by the progressive editor of The Appalachian, students went on strike due to the strict social restrictions of men and women being seated separately at basketball games. On February 12, students protested into the night at the dormitories, and the next day, students with picket signs blocked doorways, prohibiting peers from attending classes. College President B. B. Dougherty met with the senior class students in an effort to quell the unrest. Students and teachers were to work together to plan upcoming programs.

Later that year, President Dougherty allowed female students to select which days they could travel uptown and when to visit the soda fountain, department stores, and other Boone businesses. Female students would continue to get additional rights through the years.

In 1939, the Student Council revised the rules on dating and the number of dates that women were allowed. The number of dates was delegated by class rank: seniors were unrestricted, juniors were allowed three per week, sophomores were allowed two, and first-year students were allowed one. In 1945, the first “Leap Week” was held, where women asked men for dates and paid all expenses.